A quick look at a key swing factor for the global economy

[4 minute read]

Having been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world for the last 40 years, China is now growing slower than the US. That’s even more galling as the MSCI China has only returned barely more than 1% a year since 1992!

The bottom line is now this: China’s property bubble is deflating. A massive debt supercycle is unwinding and it’s hitting Chinese consumers. China recently stopped reporting youth unemployment once it exceeded 20%.

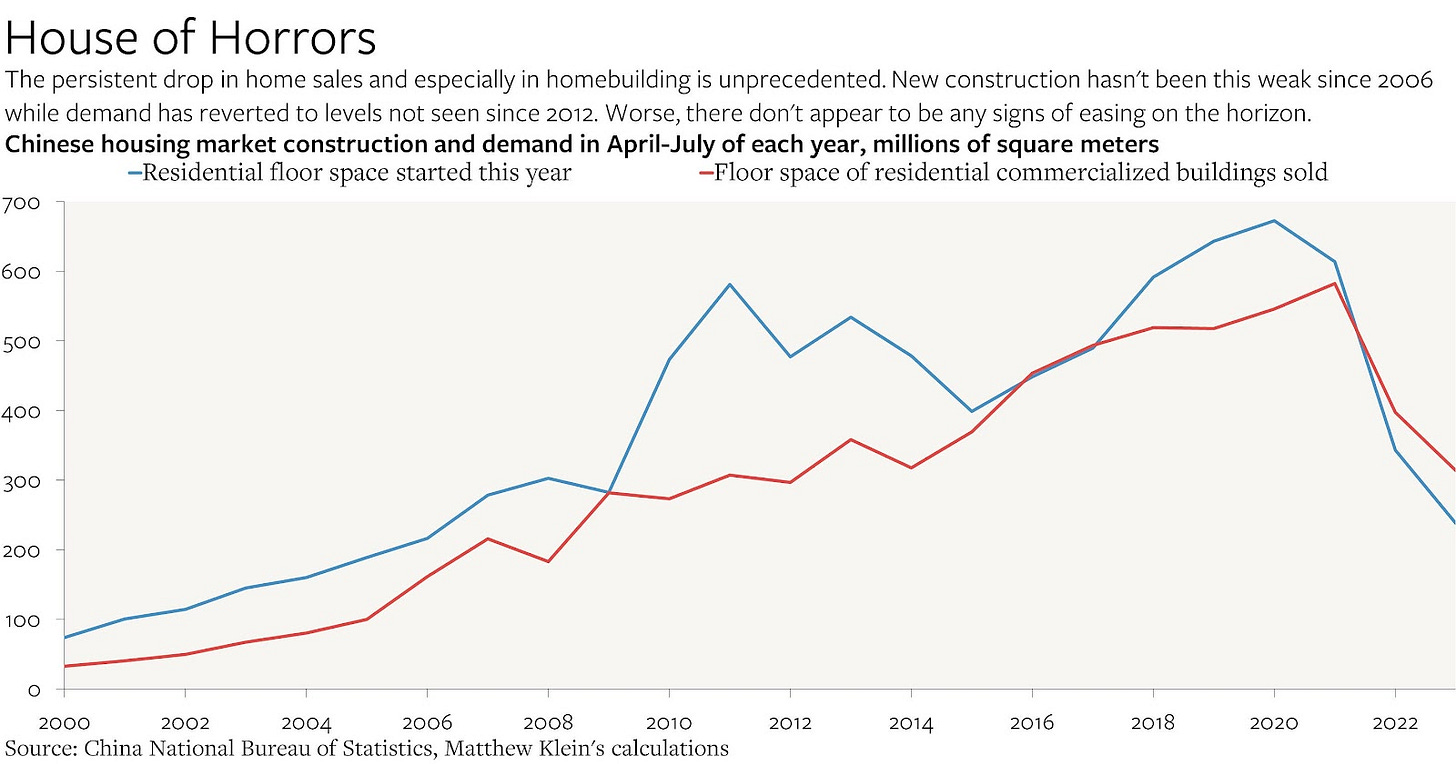

Economist Matthew Klein just did an excellent brief chart rundown of what’s going on:

Chinese housing has long been overvalued because it was the preferred savings vehicle for retail investors. That inflated construction activity and reduced affordability for families. After years of proclaiming that “houses are for living in, not for speculating with”, the Chinese government finally decided to make a point of squeezing the sector in 2021.

Housings starts have since plunged 65% from the peak in 2020, while sales are down by 43%. The best that can be said is that the pace of decline seems to be decelerating slightly, although activity in April-July 2023 is still down by 20-30% compared to 2022.

The knock-on effects for the rest of the economy – and the rest of the world – have yet to be fully felt in part because builders continue to be working through a large backlog of unfinished projects. Housing completions are still chugging along at more or less the same rate as they have been for years. Sales and starts have been persistently higher than completions because most homes are purchased in advance and because the market has historically grown over time.

But if sales and starts fall enough for long enough, builders will eventually work through that backlog and have to cut back their production. That would end up hitting construction employment, Chinese demand for iron, copper, and construction machinery, and more.

While good arguments can be made that the financial contagion won’t be that severe, you probably wouldn’t want to be cyclically exposed to commodities ahead of that outcome.

Friend-of-the-firm Marko Papic’s take is that the US and China have now traded places. He has consistently argued we should look at the real-world constraints politicians operate under rather than what they say. “Watch the hands, not the mouth.”

In the U.S., the “constraint” is that voters have now become structurally more open to fiscal stimulus. This has manifested in a new “industrial policy” of huge spending increases around reindustrialization, green energy and national security.

It’s curious that the allegedly “communist” country has recently been so much more reluctant to intervene directly in their own economy than America. The key political constraint for China is now keeping their growing middle classes happy.

In the West, the secular stagnation cycle post-2008 took nearly a decade to resolve. This was primarily because policymakers failed to heed the advice that fiscal stimulus was the only way to deal with private-sector deleveraging.

In both the US and Europe, policymakers stuck to monetary policy, eschewing the fiscal lever. Politics played a major role, with the rise of the Tea Party in the US and the austerity fetish in Europe delaying the fiscal response. Once populist outcomes began to mount – particularly in the monumental year of 2016 – the fiscal lever was re-engaged with gusto.

In our view, it is unlikely that Beijing will wait seven years (as the West did) to cycle through such a rate cuts-QE-fiscal stimulus playbook. Political pressures are already building, with youth unemployment and household income indicative of a deep domestic malaise.

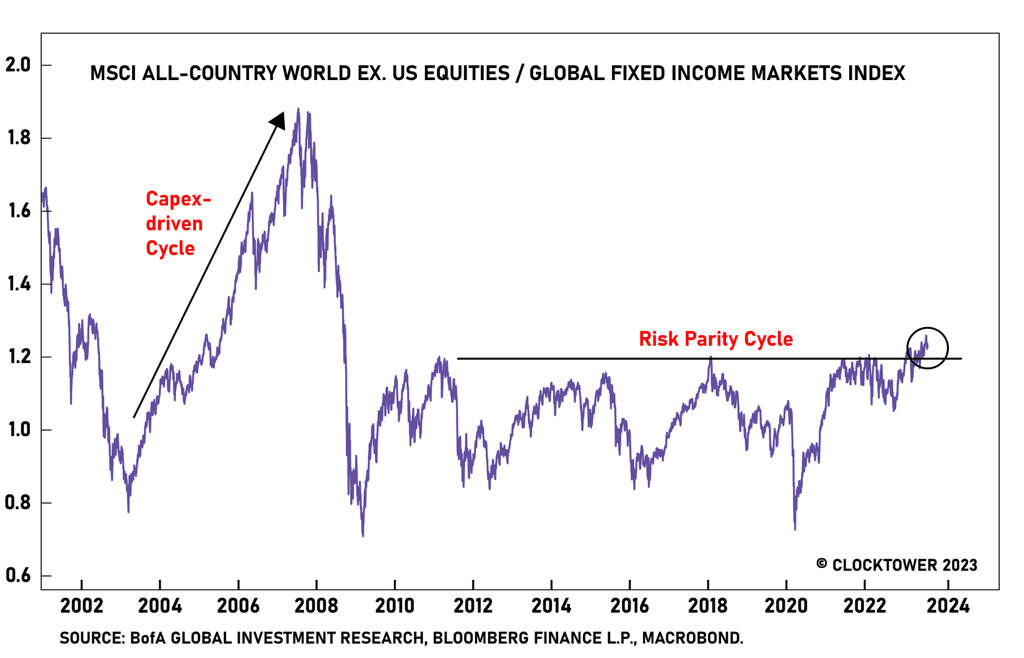

Ultimately, the West responded to its own balance-sheet recession with stimulus. China will as well, but likely on a faster time horizon. When that moment comes, it will combine with the investment boom in the US to create a significant capex-led cycle.

Such cycles tend to be positive for global equities and commodities and negative for bonds (chart below). The exact opposite, in other words, of what worked during the post-GFC, secular stagnation, “risk parity” cycle.

The “paradox of the decade” we’re focused on at Sapient is that the capex needs of a multipolar, environmentally conscious world are enormous. But, nobody wants to invest in capex for commodities. If Chinese are forced to join the U.S. in more aggressive fiscal stimulus, that would be a strong start.

This could ignite the commodity supercycle that we’ve all been waiting for.

Related reading:

- Read. Why China’s economy ran off the rails by Noah Smith (14 minute read)

- Why read. A quick simple explainer from economist Noah Smith, that handily links to other explainers.

- “China basically pivoted from being an export-led economy to being a real-estate-led economy. Real-estate-related industries soared to almost 30% of total output.”

Another big thing catching our attention:

- Listen. Here’s How the New Weight Loss Drugs Could Change Everything on Odd Lots, (1 hour listen)

- Why Listen. In case you’ve missed it, there is a new class of seemingly-effective weight loss drugs. I am always firmly in the “this will probably cause hidden side-effects” camp with these kinds of things. But, as Covid demonstrated, we’re not good at having nuanced public discussions about complex trade-offs. Especially when 42% of the US population is already obese.

- van Geelen: “If you’re above 30y/o & morbidly obese, and a drug was guaranteed to give you thyroid cancer in 40yrs but also guaranteed to bring your BMI back to a normal range, it would still be a net positive on your life expectancy.”